01 juin 2025

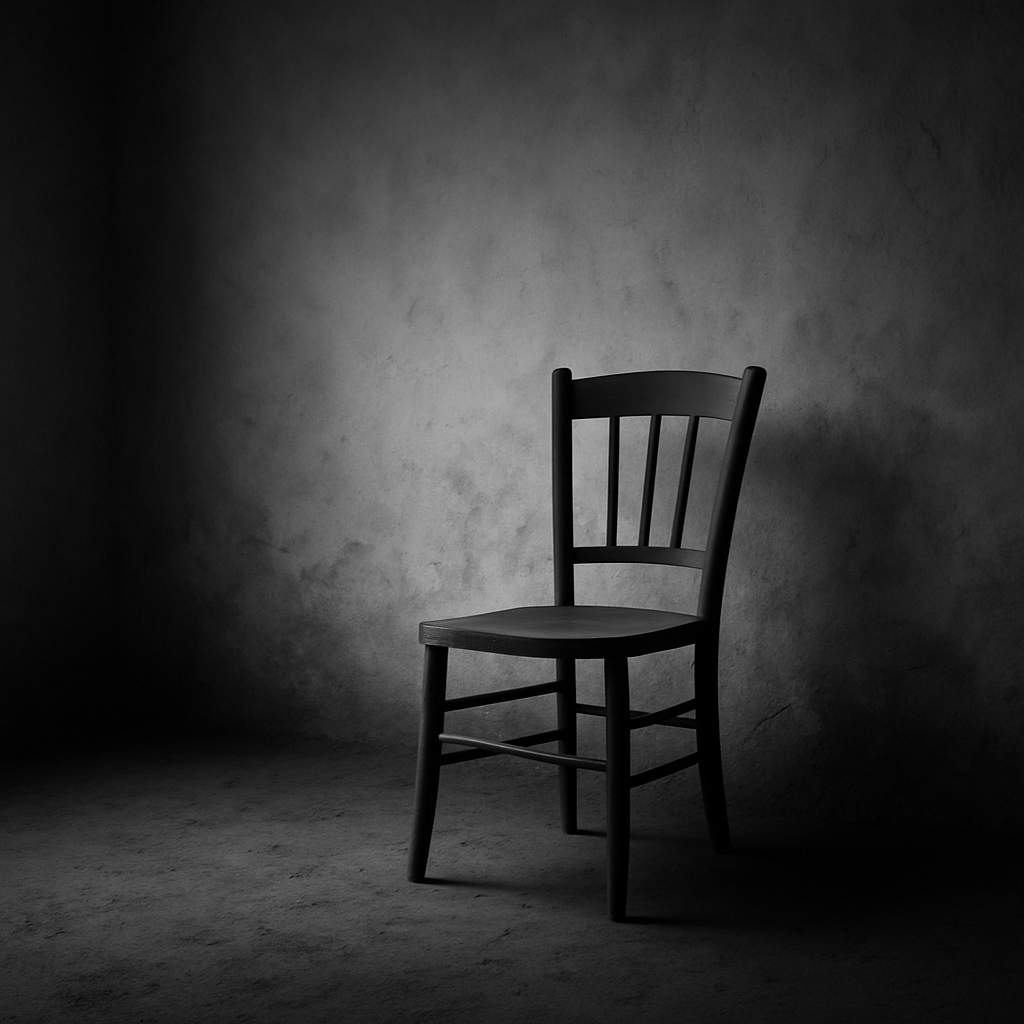

Le désœuvrement, vois-tu, ce n’est pas l’ombre au tableau, ce n’est pas le creux honteux des jours. Ce n’est pas ce terme péjoratif dont la langue sale des vivants use pour masquer leur peur du vide. C’est un mot d’atelier, un mot de vieux travailleur aux mains gercées et à la voix rauque, un mot aussi noble, aussi plein que menuisier, que forgeron, que manœuvre — car il dit une absence, certes, mais une absence qui travaille en dedans, qui modèle l’âme comme le vent sculpte l’arête des collines.

Pourtant, j’entends encore la voix de ma grand-mère — celle du côté de mon père — et je me demande, à l’instant même où je l’écris, si c’est sa voix véritable ou bien une voix forée dans le silence par cette page, une voix de papier et de mémoire mêlés. Elle disait : les désœuvrés, comme on dit les damnés, les oubliés, les sans-place. Ce mot lui servait d’ombre portée, de contre-jour. Elle n’aurait jamais dit clodo, moins que rien, débile — c’étaient des mots trop crus, trop modernes. Elle préférait celui-là, antique, engourdi comme une pièce dans une poche de laine.

Le père de mon père, lui, disait simplement : pauvre type. Dans cette expression, il y avait déjà une façon d’amortir la chute, une sorte de compassion musclée, de pitié virile — ce qu’on appelait, dans le canton, l’euphémisme.

Pourquoi je retourne dans ces recoins obscurs ? Ces vieilles histoires, ces éclats de souvenir contiennent peut-être, sous la poussière, une clef, une écharde, un fragment de ce qui m’échappe aujourd’hui. Un embryon d’explication. Un tesson d’oracle.

Cette nuit, j’ai laissé la fenêtre du bureau ouverte. À l’aube, cinq heures, un chant. Non pas le chœur clair et limpide auquel on croit encore à demi en rêvant, mais un concert maigre, tranchant, comme taillé dans du cuivre. Il y avait un soliste — je le reconnais à sa constance — et deux ou trois autres, plus hésitants, qui lui répondaient. Srii-srii. Une trille, peut-être, un mot qui monte du fond des dictionnaires oubliés.

Ce n’est pas un chant joyeux. D’habitude, on dit que le chant des oiseaux à l’aube met en joie — hier encore je le disais. Mais cette fois, non. Ce n’est pas de la joie. C’est le faux effet, l’automatisme d’une publicité ancienne. À force de croire que ceci produit cela, on finit par entendre faux.

Donc, je ne suis pas en joie. Je ne suis pas triste non plus. Je suis entre les deux, dans cette zone d’indécision, dans l’entre-deux des états et des gestes. Au beau milieu du désœuvrement, comme un homme debout dans le courant, sans rivage.

Idleness, you see, is not the blemish on the canvas, not the shameful hollow of our days. It is not that pejorative term, sullied by the mouths of the living, those who use it to veil their dread of the void. No, it is a word forged in workshops, hammered out in the chapped hands and husky throats of old laborers ; a word as full and solemn as carpenter, as blacksmith, as hired man — for it names an absence, yes, but an absence that labors inward, that shapes the soul the way the wind chisels the ridge of a hill.

Still, I hear my grandmother’s voice — my father’s mother — and I wonder now, in the instant of writing it, if it is truly her voice or one hollowed from silence by this page, a voice made of paper and memory mingled. She said the idle, as one says the damned, the forgotten, the place-less. That word was her penumbra, her chiaroscuro. She would never have said bum, good-for-nothing, half-wit — too raw, too modern, too cold. She chose instead this one, ancient and numbed, like a coin lost in a woolen pocket.

My grandfather, on the other hand, my father’s father, he said simply : poor soul. And in those two words there was already the softening of the fall, a kind of masculine pity, an old-county euphemism, a way of naming without wounding too deeply.

And why do I return, then, to these murky corners ? To these old stories, these shards of recollection — perhaps because within them, beneath the dust, lies a key, a splinter, a sliver of what now eludes me. The embryo of an explanation. A broken oracle.

Last night I left the window open in the study. At dawn — five o’clock — a sound. Not that clear and limpid choir one half-believes in dreaming, but a meager, cutting concert, copper-hewn. There was a soloist — I knew him by his persistence — and two or three others, hesitant, answering back. Srii-srii. A trill, perhaps, the word dredged up from the sunken lexicons of forgotten dictionaries.

But it was not joyful. We say birdsong at dawn lifts the heart — I said it myself, only yesterday. But not this time. It was not joy. It was the counterfeit of joy, the rote effect, the worn-out echo of some old advertisement. Keep repeating a thing and soon the hearing fails.

So no, I am not joyful. Nor am I sorrowful. I am somewhere in between, that halfway land of gestures and states, that middle distance. I stand in the center of my own idleness like a man caught midstream, and no shore in sight.